803 – 805 ASF

When I attended my first ever lecture on Rugon Craythe, Lorekeeper Chrasse strode into the hall sporting a metal skirt, clinking beneath his robes. “I look funny, don’t I?” Chrasse exclaimed to us. “Well, that’s what everyone else thought of Rugon. Then he went on to conquer them all.”

I soon learned to expect oddities like this out of Chrasse. But during my trip to Great Forks with him, his odd behavior began to pile up. I heard him coming and going at strange hours of the night. He staggered in late to his own meetings, forgot about which tasks he’d given us. Dark bags grew beneath his eyes. All of this on top of how he guarded a morsel of knowledge I wanted more and more to learn: Rugon’s secret.

Perhaps, I thought, I’d discover it on my own, so I redoubled my efforts in learning about the first King of Rivona. Rugon the Ruthless may have carried a secret while establishing his new kingdom, but how he kept it stable thereafter was hardly a novel concept.

A fist. An iron one, crushing all resistance and taking what remained. He executed chieftains while their tribes watched. He stole wives, mothers, daughters—for a night, for a week, or even forever. He made horrific public examples of traitors and criminals, often with creative punishments that matched the crimes. For example, Rugon was known to have an affection for ravens and declared them protected under royal law. When one of his bowman used one for target practice, Rugon strung him to a pole, flayed him to an inch of his life, then left him to die, letting the ravens have their fill.

For all his crushing and taking, Rugon was at least wise enough to share with his allies and people. He poured most of his wealth back into his conquered lands, building long-lasting bridges, roads, and strategic ports up and down the many rivers. He raised a great castle at Great Forks—and as a city sprang up around it, he enclosed it in powerful walls, cementing it as a seat of royal, cultural, and economic power. He even progressed the craft and style of men’s skirts. (Alright, confession, I fabricated that last one. But nothing suggests Rugon stopped wearing skirts in this time—and fashion, like most else, follows the king. So tell me, is it so flimsy a speculation?)

But perhaps Rugon gave too much. When the King sired his firstborn heir, a healthy young boy, he ripped the child out of his mother’s arms and cast him into the river—and in doing so, shocked the entire realm. Sending the deceased out onto the water was a custom that predated Rivona, but Rugon had now twisted this into a new tradition. It was an offering to the rivers and ravens for their continued blessing. He sealed it with a decree, a firstborn sacrifice required of all his successors.

The practice soon became called “giving to the river”. It does not survive to this day, but it survived much longer than it should have. Long enough that I could still personally see its impact on my time in Great Forks.

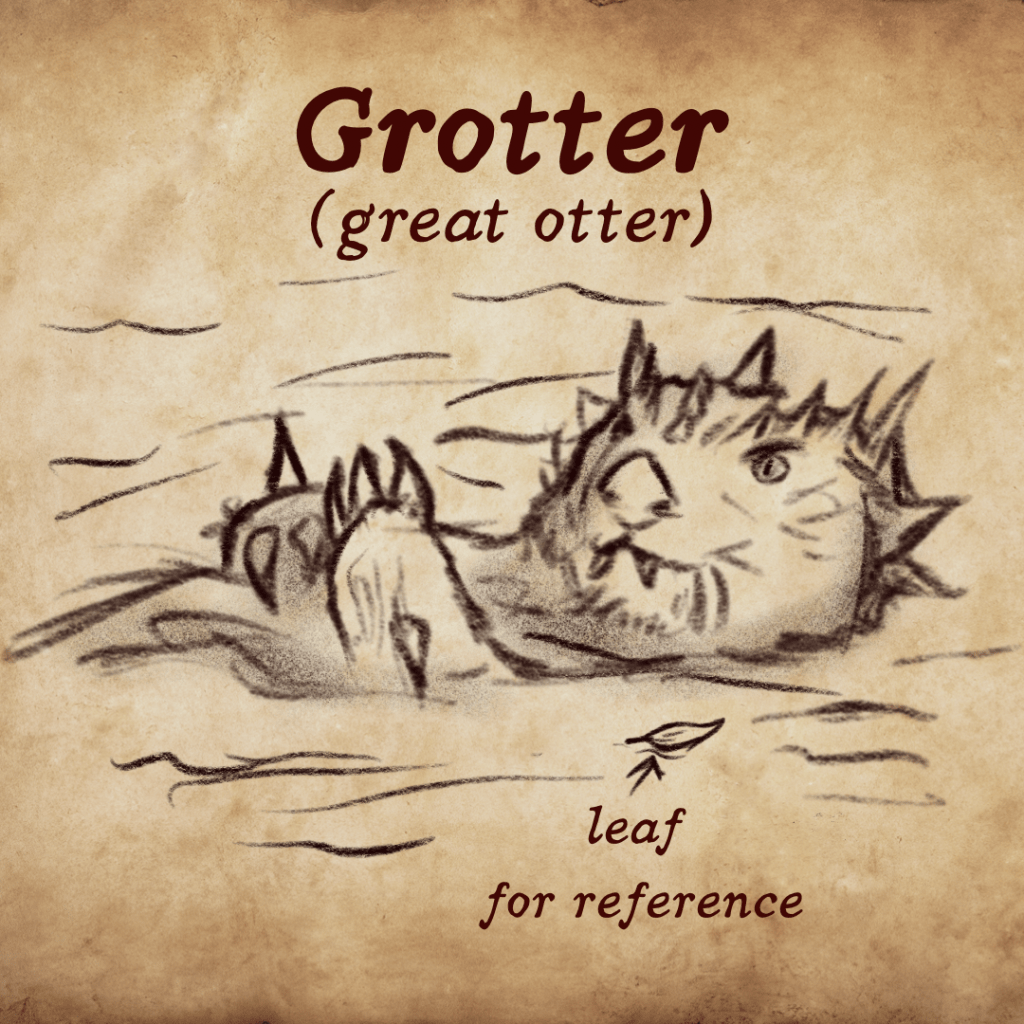

Grotters—“great otters”, which can grow large and strong enough to flip a fishing boat—have long infested the waters surrounding Great Forks. Forkians will yammer on and on about all the trouble they cause, but did you know this wasn’t always the case? Deep lakes and warm marshes are the normal habitats of these creatures. Most naturalists believe they were drawn to the Great Forks area in the days of giving to the river. A haunting thought, to be sure, but the grotters never left, even after the tradition was outlawed.

As I soon saw myself, the grotters spend their days hunting for whatever the city dumps in the river, and will still go after people and animals if given the chance.

Something that was not lost upon Lorekeeper Chrasse. He was a burly and collected man, yet one driven to sweats and shakes whenever we crossed a bridge over these creatures. Imagine my surprise when, while on an evening stroll, I spotted him from afar on Grotter’s Bridge, the best location for viewing in all the city. Slipping into a nearby alley, I studied him for a while, watching him pace and pace and pace until a hooded figure emerged from the crowd. The two men made an exchange—something glinting in Chrasse’s hand for a sack of coins—so quick I would have missed it if I hadn’t been watching closely. In the next blink of an eye, the figure had vanished.

I pretended to bump into Chrasse as he was coming off the bridge. When I asked him what he was doing here of all places, he claimed he was feeding the grotters. But what, I pressed, about his very valid and very healthy fear of them? His reply: the locals said it was a sign of good luck—and couldn’t we all do with some now?—and by the way, how were those copies of The Lover’s War coming along?

That was when I noticed that his University seal—a silver brooch worth a decent sum of money—was missing from the front of his jacket. Something was not right here, and it wasn’t just Chrasse’s blatant lie.

Many scholars remain baffled as to why Rugon sacrificed his firstborn son and began the tradition giving to the river. Did he buy into Rivonan superstitions about the power of rivers and ravens? Did he fear them? Was he beseeching greater powers for peace and prosperity, or did he feel obligated to give back after all he’d won? Or was he simply asking for more good luck?

Whatever he wanted, Rugon got none of it.

Leave a comment