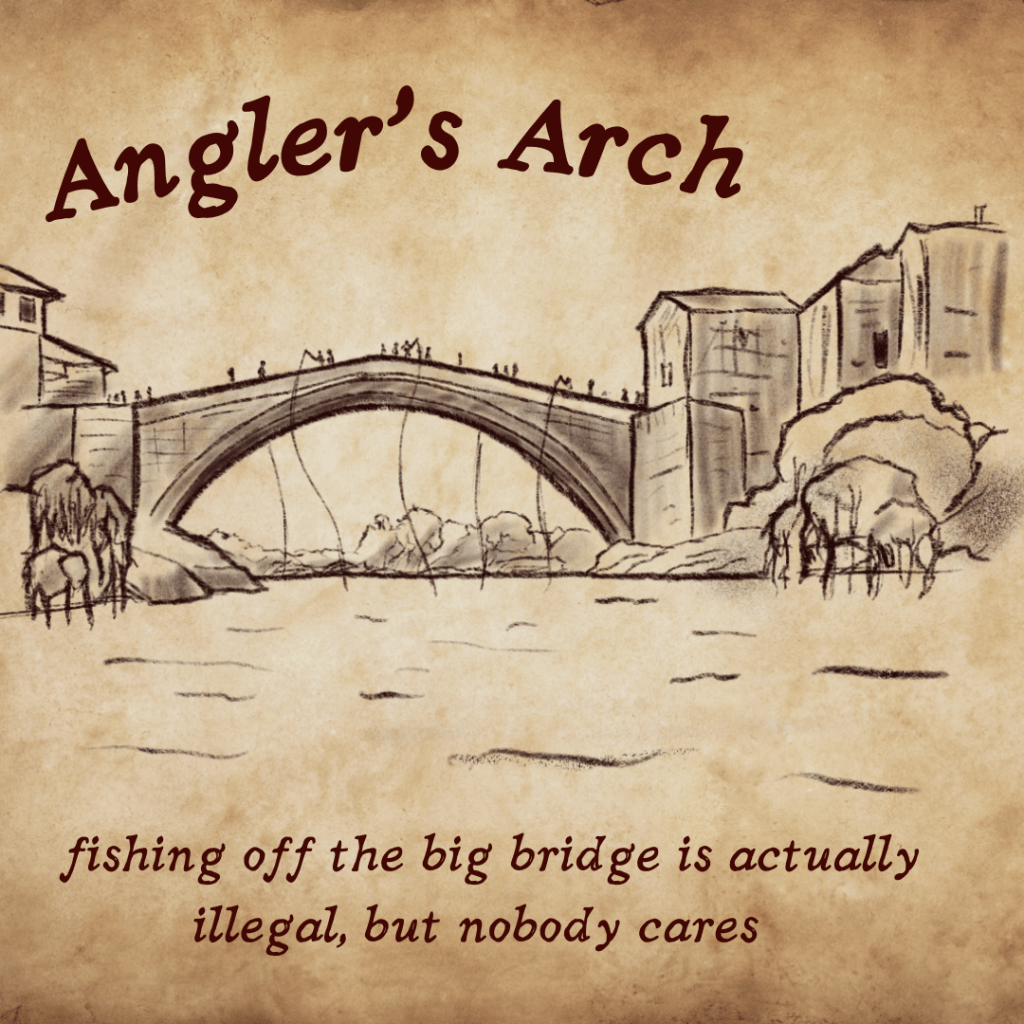

879 – 937 ASF

Not all riverbirds were good.

Or at least, this was what Dallyn and the townsfolk of Angler’s Arch believed. After living with Arlisse and learning the story of the Riverbird Traitor, I struggled to adopt this view. It was hard to picture riverbirds as anything other than caretakers of the waterways; a force of benevolence that made Rivona cleaner and safer. So how had bad blood festered between the town and its local riverbird, Jayne?

At first, I thought it was a classic case of misplaced suspicion. Falsely accusing a riverbird of witchcraft was practically a Rivonan tradition, after all. Arlisse had warned me as such, telling me that distrust in riverbirds tended to increase the closer a town was to Great Forks. Even if you take out superstition, most city-dwellers didn’t understand a riverbird’s connection to the wilderness, often feeling they got in the way of trade and fishing. And Angler’s Arch was a hop and skip away from the city.

Yet the trouble with Jayne seemed more than repeating history. Over the next several days, over the period I worked in the guard barracks beneath Dallyn, Jayne struck back against the town, most of the time at night. She raided a store of its herbs, opened the horse stalls, and even stole someone’s cat, sneaking in and out before the guards could find or catch her. The riverbird, it seemed, was earning her fair share of collective anger and hatred.

Some of that reflected onto the new woman in town. Me. With my history with Arlisse, Dallyn distrusted me, which meant every guard beneath him did, too. I slept on a cot in a room with three other women, neither of which uttered a single word in my direction. Nobody sat next to me in the mess. In hallways, guards gave me wide berth, as if I carried a case of Everscratches. Arguing or challenging any of this, I figured, would only cast more suspicion onto myself.

Not to worry. The story of Kerraguard-Captain Harland and the Somber King kept me busy. As I continued to sift through the chaos of the record room, I found more loose papers on the events that unfolded—and on Harland himself.

Harland and I shared a trait: we were both terrible fishers. As a young man, Harland struggled to snag even a single painted salmon from the bridge that was the namesake of Angler’s Arch—a bridge famous for its easy fishing. He did, however, hook the attention of a young woman, who fell in love with him despite his lack of skill.

Determined to start a family with her, Harland found a job as a dockhand, hauling cargo and catch to and from river boats. Before long, he married and started a small farm with his wife on the outskirts of town. They enjoyed several good years together, but it was not to last. Complications with birth claimed the lives of both his wife and newborn son.

As the Rivonans say, the Raven roosted in his home. After such a tragedy, many search for solace in their cups, gambling, or other vices. Harland, however, walked it off—but not in the way you’re thinking. Unable to live in a home cursed by such grief, he abandoned the farm and returned to dock work. At the end of each and every day, he walked along the river until late at night. Townsfolk and river crew often found him sleeping amongst boulders in the morning. For years he lived in this way, seeking nothing save a meager living and his daily walk along the riverbank.

Only one thing shook him from his trance. When the queen and her firstborn son were assassinated in 906 ASF, Harland answered the call to war. To understand why, we only need to look at his record. The king’s war of vengeance turned many into butchers and animals, but not Harland. In any skirmish or battle, his priority was to save his fellow countrymen and soldiers—a trait he lived to a fault. During the Battle of Hawkfalls in 907 ASF, Harland ignored orders to capture an enemy officer, instead rescuing several hostages from a burning tower. He saved their lives, yes, but the officer got away.

In many respects, Harland was a terrible soldier—but he had the makings of a Kerraguard. After Hawkfalls, the Kerraguard-Captain took note and invited Harland into the fold. His duty would not be to slay enemies or capture fortresses, but to—above all else—protect the royal family. After a year of arduous training, Harland was inducted into the order and assigned to Rogar Craythe, the second born son who would become the Somber King. At the time, the boy was only eight years old.

This meant that, over the years, Harland personally saw the boy wither from neglect, guilt, and the weight of a crumbling kingdom that would soon fall upon his shoulders. Harland did all he could: training with the boy each day, sharing meals with him, lending an ear to his complaints and woes. This was no substitute for the love and bond of the boy’s father, who was too preoccupied with grief and vengeance. But Harland dare not overstep that boundary. His duty was to protect Rogar, not to be a father to him. Even if he may have wanted to.

Just as well, my duty was to organize Dallyn’s record room and keep my mouth shut. But after several days of being shunned by the entire barracks (even the resident black cat ignored me, but that might have just been a cat being a cat), I confronted Dallyn. One evening, when he came to check on me, I asked for an explanation. Not for why I was shunned, but for the situation with Jayne. As for why I wanted to know: maybe I could talk to her, convince her to stop her attacks.

Dallyn laughed dry, invited me to be his guest, and indulged me. Several months ago, he said, Jayne had shown up in town and introduced herself as the new local riverbird. She’d demanded food, herbs, and supplies to set up her new river hut upstream. Nobody had donated—for Angler’s Arch did not want or need a riverbird. Frustrated, Jayne had left, then returned a few days later, demanding alms, only to be denied again. The third time Jayne came back to town, she carried a threat—that without her, the river would surely muck up and become a graveyard for fish.

To this, the townsfolk had told her to go upstream or get lost. Jayne’s attacks had started shortly afterwards.

Now that Jayne had established herself as a criminal, the local lord had tasked Dallyn with capturing her and bringing her to justice. When I heard that, a chill ran down my spine. What did that mean? We would just have to see, Dallyn replied, but if I could talk her down, then by all means. He wouldn’t be holding his breath, though.

“Not all riverbirds were as good as you want them to be, Elandra.”

I was undaunted. Perhaps there was something more I could do in Angler’s Arch than sift through old paper.

Harland must have felt similar, when the boy he vowed to safeguard transformed into a man who “accidentally” fell into the river. Harland wanted to do more than just act a bodyguard—he had to, if he wished to protect the Somber King from himself.

For the first time in his long years of service—and his entire life—Harland played the part of a father. Instead of merely listening, Harland offered his opinion, his advice, even plans of action. Rogar dismissed these, claiming that every path before him was doomed. Harland switched instead to questions that probed at the king’s mind and heart, but this only made Rogar clam up. With growing frustration and desperation, Harland urged the king to seek out joy in an interest or passion—fishing, hunting, or falconry, for example—to balance out the dark news that plagued his court, day by day. Rogar refused—what point was there in seeking happiness, when it was only a matter of time before the wolves closed in?

Nothing worked. Harland did not have experience as a father, after all. Or perhaps he pushed to king too hard. At his wit’s end, Harland made one last exasperated suggestion: to walk the river each day, to listen its sounds, to feel its cool water—as Harland had, after losing his own family. Hearing this, seeing his Kerraguard so distressed, Rogar finally listened.

You might think this was a turning point. It was. Just not in a positive way. For it was along the river, during these walks prescribed by Harland, that Rogar met a riverbird.

And, according to the loose pages I had scavenged, she would come to be known as Bloodhawk.

Not, I presumed, a good riverbird.

Leave a comment