The seed, half-buried in the cool dewey soil, winked up at him.

Russal scrunched up his brow and plucked the seed from the earth, staring at it between his two dirty fingers. Shaped like a tear drop, it was about as big as his thumbnail and… purple? Purple as fresh lavender. Purple, with little pinkish streaks running across its surface.

“Odd little thing, aren’t you?” he said. “Alright, fess up and identify yourself.”

The seed did not respond.

“Now don’t play coy with me.” He pointed up towards the branches of the tree above their heads. “The jig’s up. You’re clearly not cousins with Lady Apple here.”

No response except the chilly autumn wind, rustling through the leaves.

“Plum?” he questioned it. “No, let me think—erm, barley.” He shook his head. “No, you’re too delicate. Too pretty. Maybe. . . a griffon peach? Only met one of them before, off the back of some trader’s cart.” He brought the seed up to his narrowed eyes, whispering. “Or you’re some gnarled shiteweed that’ll take over half a pasture when nobody’s looking. Well, I say to you, little seed, not on my watch.” He paused for a moment. Then: “But let’s see, shall we? I’ll give you a chance.”

He dropped the seed into a jacket pocket.

As he did, a strange sensation prickled down his neck and spine. The feeling that someone was watching him.

He rose on his muddy leather boots and looked around. Nothing but open briar country—weedy and yellow and strewn with knee-high patches of briar— surrounded him and Lady Apple. He’d be able to spot anyone between here and the twinkling lights of town in the south. Nobody was. Which meant…

He turned north, towards the border of the Deep Bramble. A gloomy forest of spindly birch and great gnarled oaks, of thorny vines and briar patches as large as a houses. Sunless, labyrinthine, and scattered with patches of changing leaves, the Deep Bramble grew wild against the northern horizon as far as Russal could see.

Had someone been watching him from there?

Folk did say the Deep Bramble was home to forest spirits. Fae. They roamed the prickly depths, tending to trees and thorns and poisonous plants. If they had things their way, they’d cover the earth in brambles, so they said. But above all, they hungered for the human soul, a sweet nourishment for their magic, so children would do well to stay clear. At least, that was what his mother, Orlia, had told him since he was a little lad. Regardless of how true it all was, nobody ventured into the Deep Bramble.

Russal shivered in the wind, chilly fingers slipping up under his shirt. Best to be getting home.

Slinging his rucksack over his shoulder and putting his back to the forest, he started towards town. He felt a pang of guilt about the seed, as if he’d picked up a gold coin dropped on the street. But this seed didn’t belong to anyone. It wasn’t secondhand thievery. Plus, the seed would never thrive in territory already belonging to Lady Apple. It needed a new place to grow, and Russal had promised it a chance.

He cut across the briar country and took the northeast road into Thornbrook. Patches of prickleweed lined the dirt path, their surface roots reaching towards each other across the way like little thorny outstretched arms. Russal knelt down and ripped them up with his hand rake. “Little bastards,” he grumbled, shaking them into his rucksack. “Go make your love somewhere else.”

The prickleweed would grow back within a day. So did most other things Russal rooted out around town. Good thing they did—it had provided him a steady job for more than half of his thirty one winters. If not for him, the weeds and vines and briars would overrun everything, from the houses to the fields to even Lady Apple. It was a problem Thornbrook had had since its founding. No matter. He enjoyed the work. He never tired of the wet pop of an uprooted plant, as satisfying as a cracked knuckle.

Russal raked up a few more vine-crossed lovers before making it back into the town square. Only a few folk were out and about. Most everyone had already buggered off indoors after sunset. Normally he skulked his way around the edge of the square, avoiding folk—but stopping to weed, of course—on his way back home.

Instead, he slowed his steps, gazing over at the merchant wagon parked on the far side of the square. There, a young woman was closing up shop, packing away a variety of trinkets and baubles into boxes. Elendra was her name. He’d overheard it. She and her father had come into town a few days ago. The old man was nowhere in sight—probably off to the tavern.

Good for Russal. Lucky for Russal. Now all he needed to do was not shrivel away like a gods damned tomato in the summer heat. No more excuses. She might be gone tomorrow. Straightening his jacket and setting down his rucksack, he went over to the wagon. He wiped his dirty hands together as he approached. He had once heard that women appreciated this gesture. It was proof of a hard worker. Which he was, of course.

It worked to some degree. As he neared, Elendra looked up at the sound of dusty, calloused skin sliding together, and frowned at him. Perhaps she was wondering what rough, gritty job had tarnished him so. Well, he would tell her. If she asked, that was.

“Sorry, sir, we’ve closed up for the night,” Elendra said. “We’ll be open again tomorrow morning.”

“Oh,” Russal said. “I, erm… hmm.” Gods, she was pretty as a sunflower at full bloom. Green eyes. Freckles. The swish of her brownish-blonde hair as she’d turned had smacked the words right out of his mouth. He didn’t know what to say. Damn.

And while his tongue had tied itself up, he’d kept on wiping his hands together. Elendra raised an eyebrow at this. “Uh…are you alright?”

Russal jammed his hands together behind his back. “Er, yeah. Very busy day. Very busy.”

“Uh-huh,” she said. “I see. Well, I heard the harvest was good this year.”

“Oh gods, no, I don’t do any of that. I’m the town weeder.”

She tilted her head. “You… pick weeds?”

“Indeed. All day, every day.” He jabbed a thumb at his rucksack. “That’s today’s catch.”

“That’s all weeds in there?”

“Yeah and a few small children, too.”

She gaped at him. “What, really?”

“Nah. I’m the town weeder, not the tax man.”

And by the grace and fortune of the woodland gods, she laughed. At the clear sound of it, his rolling stomach turned itself upright and blossomed with joy. Like a festival performer tumbling and tumbling before snapping himself upright in a graceful flourish. He laughed with her. Not wanting to spoil his recovery, he gestured to the half-packed boxes. “What sort of things do you sell?”

“Anything and everything, really. You wouldn’t believe some of the strange things people part with.”

“So you buy things, too?”

“Well, trade. Something of mine for something of yours.” She glanced at his rucksack. “I suppose you find things when you’re digging up weeds?”

Russal’s hand hovered over his jacket pocket containing the purple seed. Yes, he wanted to say, I found this just today. Isn’t it pretty? And yet something wriggled through his heart at that very moment, like a worm through an apple. He found that, actually, he did not want to give up the seed at all. It was his. Not hers, or anyone else she’d sell it to. He had made it a promise.

He moved his hand away and shrugged. “Just weeds today,” he said, then quickly added, “Though I do have a small collection at home. I happen to be a finder of strange things.”

She smiled. “Well, we open at sunrise tomorrow. Why don’t you bring some of your things by?”

“Could do that,” he said. “What do you want to see first? I’ve got an old clay mug, but I wouldn’t recommend drinking out of it. A copper bracelet, but it’s a bit missing a link. Oh, and a wood carving of a fae.”

Elendra’s eyes sparkled. “Oh, the carving! Please bring the carving. I’m fascinated by the tales of the fae around these parts.”

“Well, I—”

“There you are, Russal!” a new voice cawed.

He cringed. He turned to see his mother, Orlia, waddling from the door of the tavern over to the wagon. She was a tiny, twiggy woman, but you’d never know it from the countless layers of patchwork cloaks and lacy shawls she bundled herself up in. Faded red hair fell like parched vines from out of her hood. From somewhere within her woolen bulk she pulled out a mug of beer and took a swig. Stumbled, spilled a bit on herself. “Be a dear and walk your mother home, won’t you?”

Gods damn it all. Russal gave Elendra a nervous smile, fully aware of the type of first impression Orlia bestowed. “Mother’s had a long day.”

“Oh, I… understand,” Elendra said. “Father’s in the tavern too.” She glanced at her wagon. “Perhaps I should be going.”

But Orlia staggered up to them both, sticking her nose over the remaining boxes as if she were some discerning merchant or cultured collector of rare artifacts. “Now, what do we have here?”

Elendra picked up one of the boxes and placed it in the cart. “I’m sorry, miss, but we’re closing up shop. We’ll be open tomorrow.”

Orlia shook her head and tsked. “I’m afraid you won’t get far if this is how you treat potential customers.” She tapped one of the boxes with her boot. “The odds are already against you with this junk you’re trying to sell.”

Elendra recoiled, as if slapped. “Erm, well…”

“Mother!” Russal pulled on one of Orlia’s arms. “That’s no way to—”

“Hush. This woman’s trying to squeeze you of all your hard-earned coin.”

“But—”

“Hush! I won’t say it again!”

“Actually,” Elendra said, “It was the other way around, miss. I was offering to buy off him.”

“Oh I’m sure you were,” Orlia snapped. She tilted back and emptied the rest of the mug, then flung it off to the side.

“It’s true, Mother,” Russal said, going over to the bushes to retrieve the discarded mug. “I was going to bring by a few things tomorrow.”

“Don’t waste your time,” Orlia said, but this was directed at Elendra. “Russie here has enough friends. He spends all day talking to plants. Did he tell you that?”

Elendra opened her mouth, closed it, fumbling for something to say.

“Mother, that’s enough!” Russal cried. “I—”

“Hush,” Orlia snarled, and she raised a thin, spotted finger at him. Russal flinched, her gesture piercing the heart and bleeding out all the confidence in there. He knew what that finger meant. It was the line. Cross it or else. He shrunk back, clutching the mug to his chest.

Elendra noticed this, her wide eyes going back and forth between him and Orlia. Russal knew this look all too well.

“I think I should be going,” she said.

“Yes,” Orlia said, “you should be going.” Her pointed finger became a grasping hand. “Come now, Russie. Walk your mother home.”

———

The whole house shuddered when Russal slammed the door to his room.

“Well just go on!” he growled to the wooden bones of the walls and ceiling. “Just do it! About gods-damned time anyway!”

But it was just a house, of course, and did not honor his request to bury him and his mother alive. It was little more than several moldering rooms cobbled together, prone to leaks and blasts of cold air when the wind hit just right. There were two families of rats—at least—living under the floorboards. But it was theirs, built by his father’s father ages ago. Russal’s job brought in enough to pay the tax man, buy food in town, and cover Orlia’s tab at the tavern, but not much else than that. He was fine with this, though. It was home. It was comfortable. He had no desire to leave. When Orlia was out late and he was home alone, it was perfect.

“Why does she do this to me?” he said aloud, putting his head on the wall. He wasn’t talking to the house anymore, though. He was talking to the line of potted plants on the window sill across the room. They, unlike the house or his mother, listened. “Doesn’t she understand? She’s ruined my chances with Elendra.”

He banged his head against the wall a few times. The bones groaned again, and Orlia shouted something from the other side of the house. He ignored her and kept talking to his botanical family.

“I’m running out of time,” he mumbled. “I am. I really am. Gods, I’m older than half the trees in Thornbrook. Soon I’ll get so rickety and crusty that no woman will want me. No wife, no family, no home.” He turned to the window sill. “But how can I, when Mother—”

His face dropped at the sight of his plants. There were three on the window sill—a hardy, funnel-topped mushroom, a clump of fuzzy gnomebeard, and a brilliant red autumn fire flower. Except the autumn fire had wilted and died, its soft petals in a shriveled pile around its base.

“Ember!” Russal cried, rushing over. “What happened to you?”

He lifted the tin pot and brought her close, inspecting for signs of disease or pests. Nothing. Ember had been fine this morning, practically glowing in the morning sun. He’d never known a plant to die so suddenly.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered to the flower, and kissed one of the remaining petals gently. It crinkled off and joined the others. With a heavy sigh, he uprooted Ember from the pot, her fragile form draped lifelessly across his hands, like a doll about to fall apart. On the nearby table, he’d already put out a spare piece of burlap, torn from an old shirt, in preparation for the first frost. But he’d reckoned that was still a few weeks away. A few weeks stolen from Ember. He placed her on the fabric and wrapped her up gently. He would find a place outside to bury her this evening.

“Does anyone know what happened?” he said to the other plants as he returned them to the window sill. “Stalwort?” He leaned in to the mushroom, who had survived every winter since he was a boy. “Nothing from you, old man?” Then he stroked the frizz of the gnomebeard with one finger. “Well, Fuzzy, let’s hope you still get a full life.”

He went over to the table and sat down. Across the back of it, he’d arranged a display of finders keepers. An old hairbrush, a stick shaped like a dagger, the broken skull of a creature he couldn’t recognize, an old clay mug, the copper bracelet, and… the wooden fae carving.

Smaller than his hand, the carving depicted the form of a woman with slender, leaflike wings sprouting out her backside. The oak wood was hard and old, but still preserved fine details: her gentle expression, the points of her ears, the vines that draped across her naked body, tantalizingly covering her private parts. Russal imagined that if this carving had been based on a real fae, she would be the most beautiful woman in the world. He often wished she was real.

The carving, he now noticed, was turned and staring at the window sill.

Russal scowled. He could’ve sworn the carving had been facing forward, not staring over to his plants. It was a tiny shift, so perhaps the wind was to blame. He reached forward and turned the carving back into place.

As he withdrew his hand, he felt the seed in his jacket, almost warm and itchy like a fresh mosquito bite. He reached into his pocket and retrieved it. Between his fingers, it was cold, inert, pebblelike. Well, bugger. Was this seed playing games with him? Perhaps it was some kind of special fern or flower from the Deep Bramble. But there was only one way to really know.

He glanced over at the empty tin pot. Ember’s departure was tragic and strange and premature, but now there was now a place for this seed. . .

“Look, I don’t know about this,” he said to Stalwort and Fuzzy as he returned to the window sill. “Ember isn’t even buried yet! It’s like, I don’t know, getting remarried at your wife’s funeral. I—”

“Russal!”

Orlia flung open the door to his bedroom. In a frenzy of thoughtless panic, Russal slapped the seed down into pot and brushed some soil over it with his thumb. By the time he turned around, though, his Mother was standing there with her arms crossed and eyes narrowed.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“Just doing up the pot.” He positioned himself to block it from her view. “Ember’s dead, Mother.”

Orlia watched him for a few moments, as if deciding whether to fully believe him. Russal prayed that she did. She had a habit of pulling up his plants and stomping on them when she was angry. There was nothing he could do for Stalwort and Fuzzy, but his mother couldn’t squash the seed if she didn’t know about it.

At last she harrumphed and waved a hand dismissively at Ember. “Don’t try and distract from the issue.”

“The issue?”

“You’re never going to find a woman if you disrespect your own mother.”

Russal scowled. “Now hold on just a second—”

She wagged a finger in his face. “No no, none of that. There’s no arguing with the bare facts of it. Women see how men treat their mothers, and take note.”

“But that’s not what I—”

“Look!” She snapped. “You’re doing it now! Cutting me off. The disrespect! When will you ever learn?”

“Mother,” Russal grated, “I think—”

“I don’t care what you think you thought. Neither do other women.” She chopped one hand into the palm of another to emphasize her point. “Actions, Russal. Actions speak louder than words. And that was a poor show you put on for Elendra. You blew your chance.” She shrugged. “I wouldn’t be too upset about it, though. She’s not worth your time. She’s one of those traveling types from the city. A whore in a merchant’s costume.”

“Mother! She was nice!”

“Oh, I’m sure she was. She would’ve bent over her wagon, too, to get you to buy something.” Orlia clicked her tongueat Russal’s shocked face. “I’m surprised her father left her alone. You’re above a woman like that.”

Russal bit his tongue. Arguing with Orlia was like arguing with a wagon wheel stuck in a rut in the road. Sometimes it was best to just shut up and let the wheel go where it wanted to go.

“You don’t see these things because you’re a man.” Orlia stepped over and rubbed his arm in some form of sympathy, but Russal just found it sickening. “But I do. And you know your mother’s always watching out for you.”

Russal pulled out of her reach and looked away, into a corner of the room. Not for the first time, he thought about flinging himself into a support beam and bringing the whole house down on them both. He knew exactly which one would do the trick.

“Let’s just assume this Elendra was a good, upstanding girl and had pure intentions,” Orlia said. “Do you think she would still be interested in you if she knew about your . . . mark?”

Russal flinched, as if she’d struck him, and instinctively scratched at the spot under his left arm, just above his ribs. “Maybe she would’ve liked it. Or not have cared at all.”

Orlia gave him a sad smile. “Russal, dear, you need to be realistic. Could she have truly ever loved you, knowing you bear that mark? Could anyone else in Thornbrook, if they knew?” She shook her head, pointed a finger at her chest. “No. Only one person in this town knows who you really are and truly loves you for it all the same. Remember that.” She opened her arms. “Come here, it’ll be okay.”

She came to him, wrapped her arms around him. He returned the gesture, but only because she’d heap more words on him if he refused. Of all the things Orlia said, he hated this the most—because it was true. If anyone knew of his mark, of his condition, of his burden, well. That would be it.

When Orlia left him, he went to the window, mumbling to his plants as he gazed out into the night. The moon hung full and low, so bright it blotted out most of the stars and illuminated the dirt road all the way to Thornbrook. Russal had weeded the way this morning – as he did every morning – but ankle high weeds had already grown back, ensnarling the path.

There had always been a weeder in Thornbrook. The old codger who had taught him the ropes had said that without their work, the town would drown in wild plants and briar. Maybe it was just the nature of the land, he’d reckoned, or maybe it was the Deep Bramble trying to expand its territory. The reason didn’t matter. The work needed doing. Thornbrook needed Russal.

And yet… would they still want him if they knew? He unbuttoned his jacket, stared down at the spot above his left rib. There, amidst the pale flesh, were two patches of dark, discolored skin. The kiss of the fae, it was sometimes called. Russal had been born with it. It meant its bearer would suffer a curse of bad luck for the rest of their life. Looking back on his years, well, maybe there was some truth in that.

The faemark.

He found himself looking past the lights of town, towards the border of the Deep Bramble far in the distance. A still, silent wall of gloom, darker even than the sky above. He wondered what eerie things were happening in its thorny, tangled depths right now. Were the fae, their supple forms cloaked in nothing but shadow and moonlight, dancing through cool glades, tending to great trees, bathing in dark streams? Or were they gathered in the deepest, thorniest thicket, conspiring together to choose their next victim of the faemark?

“Doesn’t really matter, does it?” he asked his plants. The fae – even if they did exist at all – were somewhere in there. He was out here.

With a sigh, he turned away from the window, went over to the table, and picked up the body of Ember.

———

It was not the sun that woke Russal the next morning, but rather the smell of something sugary sweet.

Rubbing his eyes, he pulled himself out of bed and discovered the source of the fragrance: the tin pot holding the purple seed. A burst of vibrant, wine-red vines had grown out of the soil overnight, spilling over the edge of the pot and in a wreath around its base. Luscious flowers, with puckered pink and white petals, bloomed across the vines.

“Gods flay me,” Russal breathed. “And I thought you were a shiteweed!”

He ran his fingers along the vines. He’d never seen anything like these before. They were soft and smooth, but firm. Like a woman’s legs. Or at least, how he imagined they might feel. When his mind made this connection he withdrew his hand, a bit ashamed of himself.

“You’re very graceful, very beautiful,” he finally said to the plant. “Do you have a name?”

No response.

“Moonblossom, then.” He turned to Stalwort, jabbed a thumb at him. “Look, I don’t care if you think the name is hogwash. It’s appropriate for her.” He nudged his chin at the gnomebeard. “Fuzzy doesn’t have a problem with it. So why do you?” He pushed Stalwort into the corner of the window. “Well then you just sit over there and sulk. Fuzzy and Moonblossom can be friends.”

He left the plants on the window sill and continued about his day. Orlia was snoring loudly as he left the house and began weeding his way towards town. Despite the events of yesterday, his heart was high in his chest. The first bloom of a new plant always made him feel this way. The seed had grown blazing fast, faster than he’d ever seen, but then again, this was Thornbrook.

But his spirits took a dip when he came into town. Elendra was at her stall in the square, and when she spotted him she turned and busied herself with organizing her wagon. It was as he’d reckoned, then. Another chance blown away like a dandelion in the wind. He shuffled around the square, giving her a wide berth.

At least he had Moonblossom to think about now, and what she might grow into. His mind began to race at all the possibilities. Had he discovered some long lost herb of ancient times? Or an exotic fruit? These thoughts kept him distracted throughout his daily duties, rooting out the day’s growth of weeds all around town.

He hurried through the day, only giving Lady Apple a passing wave, rather than spending part of the afternoon napping beneath her boughs. He returned home early, skipping his usual routine and beelining straight to his room, expecting Moonblossom to have grown into something even more wondrous.

She was gone.

Russal gasped as if someone had punched him in the stomach. All the vines, all the flowers, all the beautiful growth—gone. In a moment of heart-wrenching horror he believed Orlia must’ve ripped it all out as punishment for yesterday. He dashed over to the window sill and thumbed through the soil in the pot and… there she was. The strange, purple seed, buried in the dirt just as he’d left her last night. It was as if the blooming from this morning had never happened.

“Fuzzy!” he demanded. “What the hell?”

The gnomebeard was not forthcoming, and he doubted he’d get anything out of Stalwort, who still sulked in his corner.

His eye caught a difference in his room. He turned. The wooden fae carving. It was facing the window sill. Again. More specifically, it was facing Moonblossom.

Had it been that way this morning? Shite. He couldn’t remember. But he was certain that he’d faced it forward yesterday. Had the wind moved it again? There was a way to test that, put the notion to bed. He swiveled the carving so that it faced the wall. So if it was facing the window again in the morning, then…

Then what?

The question buzzed around in his head like a summer fly as he went about his evening chores, which included watering the garden, herding the chickens into their coop, and making a carrot and leek stew for him and his mother for supper. Orlia wasn’t around, though, and probably at the tavern. Russal ate alone, then went out back behind the house, dumped the day’s catch of weeds into a pit, and set it on fire. You had to burn the weeds, you couldn’t just throw them anyway anywhere. One farmer had done just that in the middle of an empty field and a huge briar patch had sprung up overnight.

Orlia hadn’t returned by the time his fire had sizzled down into embers. Normally he’d go and get her now. But after yesterday, well, she could walk herself home. He’d get an earful for it later. Fine. Better later than now. He was too busy trying to figure out what the hell was going on with this seed.

As he retired for the night, he decided he must’ve imagined Moonblossom’s great flowering in a haze of early-morning dreariness. A deluded hope after Ember’s untimely passing. He drifted to bed, thinking of Moonblossom’s beautiful vines and flowers.

———

“Moonblossom!” he cried as soon as he cracked open his eyes and saw her blossoming vines at the window sill.

She had grown twice as much as she had yesterday. A curtain of those lovely vines tumbled over the pot and down the side of the wall, bursting with even bigger, pinker flowers. And the flowers—they were as big and soft and luscious, almost puckered out towards him. Just looking at them made him turn red as an apple.

“So, you’re a lady of the night?” he said to her, then smacked his head. “Sorry. Don’t mean it like that. I mean, you would just rather drink moonlight rather than sunlight.”

He had a feeling when he returned later, she’d be a seed again. He considered sitting here all day to see what would happen. But if he skipped out on his daily weeding, he’d fall behind and have to work twice as hard tomorrow. So he bid all of his plants farewell, turned towards the door, and then froze in his steps.

The wooden fae carving was turned towards Moonblossom.

His stomach lurched into a knot. The kind of knot it tied when talking to a pretty girl. Or was it the kind when he thought somebody was following him home?

“Well, shite,” he said. He went over to Stalwort and Fuzzy. “Something’s strange at play here, lads. Something fae, perhaps.” But what, exactly, and why? There were plenty of stories warning of the danger of entering the Deep Bramble, but none about purple seeds and carvings that moved on their own.

He leaned in to Stalwort and Fuzzy, speaking out of the side of his mouth. “I mean, look at her,” he whispered. “Moonblossom doesn’t seem dangerous to me. What if all the stories aren’t true? What if she just needed a chance to grow? Someone to believe in her?” He scowled at Stalwort. “Oh I know how you feel, but that’s just because you dislike her name. Come on, lads. Let’s give her a chance.”

He left the plants and went about his morning chores. Orlia was once again snoring from her side of the house as he set out for Thornbrook. All day his mind twisted with thoughts of Moonblossom, of the wooden fae carving, and what it all meant.

Late afternoon found him out amongst the northern fields, not too far from the edge of the Deep Bramble. While uprooting a particularly hairy fern, his eye caught something glinting in the soil. Clawing at the earth, he revealed a necklace unlike anything he’d ever seen. At the end of a long cord of dark, durable fiber was a single silver charm in the shape of a leaf. Black and brown spots tarnished the silver, hinting it had been here for ages.

The hairs on his neck prickled. He threw a glance over his shoulder, towards the Deep Bramble. As he turned he swore his eye caught the patch of paleness against the dark backdrop of the forest, but when he set both eyes on the Bramble, it was gone. His heart jolted. Had that been a person? A fae?

He waited, watched, but saw nothing else. He called out to the Dark Bramble, but his shout echoed unrequited across the silent, cold briar country.

He’d seen a fae. He knew it. He was sure of it. She was in there somewhere now. He knew not to follow, but neither was she calling him either. Was she connected to Moonblossom, to the carving? Now that he’d thought about it, he’d also uncovered the wooden fae carving out near the Deep Bramble several months ago—a discovery he’d chalked up to pure luck until just now.

A carving, a seed, and now… a necklace?

As he’d predicted, Moonblossom was back to a seed by the time he’d returned home. He placed the necklace next to the wooden carving. What did it all mean? Was there a fae out there in the Deep Bramble, toying with him? What did she want? He bent down over the silver leaf, running his fingers along the little etchings of veins.

The door to his room swung open abruptly. “Russal!” Orlia cried. “Where’s the money for—” she halted, her eyes narrowing at the necklace on the desk. “What is that?” He snatched up the necklace and put it behind his back as she marched over to him. “Russal,” she said. “Let me see.”

“It’s nothing really.”

“I’ll be the judge of that.”

“It’s mine.”

Orlia snapped her fingers and opened a palm. “Now, Russal.”

The usual threat was there, in her tone. Clenching his jaw, he brought the necklace around and presented it to her. She had to pry it a bit out of his hands, as if it were stuck to dried honey on his fingers.

“Where did you get this?” she asked.

“I found it today, buried under some dirt.”

“You’re not planning on giving this to Elendra, are you?”

“What? Gods no!” And it was the truth. But he prayed to the woodlands gods that she didn’t take this necklace for herself.

Orlia rubbed the leaf between her bony thumb and index finger. “Necklaces are for ladies,” she remarked. “There’s not another woman, is there Russie?”

“No.” He surprised himself at how fast the lie came out. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d lied straight to his mother’s face. Then again, was this really a lie? He didn’t even know for certain if this fae was even real.

“And you’re telling me the truth?”

“Honest to the gods.”

She squinted at him for a long while. It took all his will not to fidget. Finally, she made a guttural sound in her throat and handed him back the necklace. “Fine, keep it for all I care,” she said. “It’s quite an eyesore anyway.”

When the door shut behind her, Russal puffed out a breath he’d been clutching in his chest. He wasn’t sure why yet, but it felt like he was meant to find the necklace today. Meant to have it.

“Phew, lads,” he said to Stalwort and Fuzzy. “That was a close one.” He patted Moonblossom’s soil lightly. “She’s gone. You can rest well, too.”

Russal rarely had dreams, and the scant few he recalled weren’t vivid or interesting. His most recent one, half a year ago or more, was simply a sheep chewing grass in a field, wearing a knitted wool sweater of all things. He’d woken feeling dumber for having dreamed it. He often pegged people spouting about their weird dreams in the tavern as half-mad or half-drunk. He just didn’t get it.

Until tonight.

He dreamed of an endless forest bathed in moonlight, where the trees towered as tall as mountains and the mushrooms sprawled as wide as houses. Where motes of odd light and sweet, earthy scents drifted through the cool air. He dreamed of strange creatures roaming through this world—flying creatures, slithering creatures, crawling creatures—unlike anything he’d ever seen. Every now and then he spotted a pale shape in the corner of his eye, and he’d turn to see it had already disappeared.

It was her. It had to be.

He didn’t see her, but he heard her. A high, tinkling laugh, like the cheery chime of a silver bell. He smelled, her too—a scent like cinnamon and magnolia with a touch of fresh lavender—distinct from the rest of the forest. It was intoxicating. He wanted to drown in it. He wanted to…

He awoke with his heart thumping in his chest, and a light sweat covering his body. He rolled over to see that Moonblossom had bloomed once again, bigger even than yesterday. Her vines and flowers had grown up and down the walls and even out the window. What took a creeper vine a decade, Moonblossom had done overnight. And now she had borne round, ripe fruit through her vines, palish purple in color and about as big as cantaloupes.

Russal hesitated, and then gingerly placed a hand around one of them. Its skin was was soft and fuzzy as a peach, and — to his surprise — a bit warm to the touch.

He recoiled, a flurry of feelings roiling around inside him. This all seemed wrong from a lot of angles. The fruit had felt… alive. Well, more alive than a plant usually felt. He flushed with shame, somehow, and berated himself for a gesture that now seemed perverted in retrospect. And to think, somewhere in the back of his mind, he had wanted to pluck the fruit and eat it.

That was when he tasted something on his lips. A faded flavor, like the sour morning aftertaste from a night of drinking. Except this was… pleasant. Sweet. He worked his tongue, pinpointing the spicy, floral flavor. Cinnamon, lavender, maybe even a bit of magnolia.

“Shite, lads,” he said to Stalwort and Fuzzy. “I think she might be real. She gave me the carving, the seed of Moonblossom, and the necklace! I told you so. I even dreamed about her last night!” He paused, put a hand to his chin. “But… why? Do you think she’s interested in me? I mean, I’ve never heard of fae men. What if the fae get lonely, too?” He put a hand on his left rib. “What if it’s the faemark?”

Then he glared at Stalwort. “Look, fine, I know what they say about the fae and how they devour your soul.” He raised a finger towards the mushroom. “But hold on. Hold on! That’s for people that enter the Deep Bramble uninvited, and often carrying a blazing torch in hand. It’s not so different than barging into the king’s castle unsummoned and brandishing a sword, is it?” He shrugged. “What if you were invited? What if you were the honored guest of a fair lady? What if… you have a mark of passage?” He paused a moment, then waved dismissively at Stalwort. “Oh, keep your cynicism. I’m not suggesting that I go tromping off into the Bramble. Just that maybe this fae might not be so bad after all.”

A jolt of fear lurched through his stomach. If this fae was real and good and had taken a liking to him, then he had lied to Orlia yesterday, hadn’t he? Shite. Shite. If Orlia found out about the fae now, found out that he had lied, he didn’t know what she’d do. Probably destroy the carving and the necklace and Moonblossom. She’d ruin everything, just like she had with Elendra and every other woman he’d tried to court since he’d come of age.

“Gods flay me if I let that happen again,” he told his plants. He took the wooden carving and the necklace and hid them under his bed. Orlia couldn’t suspect or question or destroy what she couldn’t see. And Moonblossom, well, he could explain her away as a strange plant he’d found.

He went about the rest of his day constantly thinking of his dream about the fae. He spent longer than usual out in the fields by the Deep Bramble, hoping to catch another glimpse of her, but did not see or smell or hear anything. He returned home that evening and, as expected, found Moonblossom turned back into her seed. Even the fruit was gone. He rushed through his evening chores and turned in early, excited for what dreams the night would bring.

They were just as wild and colorful as he’d hoped. He was back in moonlit forest again, amongst the strange lights and odd creatures. And the fae, too, flitting just past his field of vision. He saw parts of her before she disappeared: the flutter of a wing, the curve of a leg, a flash of bare belly. He could never spot her full on, turning this way and that, chasing flickers of movement around colossal glades, searching for patches of pale skin between feathery grass. But the more he saw, the more he pieced her together in his mind, the more he wanted, needed, to find her.

Suddenly he was before a dead end. A wall of briar and weeds and dark thicket. He was about to give up when two slender arms wrapped around his chest from behind. A rush of her cinnamony musk blasted his nose, so strong it sent his mind spinning. He felt her bare, cool body press against his back. A kiss on his neck. And then…

… and then he woke, trembling, sweating, heart racing.

“Shite,” he said.

Then he saw the room around him.

“Gods flay me.”

Moonblossom had covered the entire wall by the window and even parts of the ceiling. Her fruits were now as big as watermelons and coated in a layer of dewy moisture. Then, with a wrench of his gut, he saw what she’d done to Fuzzy. Moonblossom’s vines had burrowed into Fuzzy’s tin pot and had drained it, seemingly, of all water and life. The gnomebeard was shriveled, gray, dead.

“Fuzzy!” he cried. It was not uncommon for plants to strangle adjacent ones in their quest for water and sunlight. But that was in the wild. These were potted. Moonblossom’s embrace of death seemed almost intentional. Stalwort, thank the woodland gods, was unharmed. Moonblossom’s vines had started curling around his pot in the corner, but hadn’t yet reached within it.

“I’m sorry,” he said to Stalwort. “You were right to be cautious. I’m sorry.” He glanced at Moonblossom. “I don’t know what’s got into her. I’ve never seen a plant act this way. Do you think it was an accident? They were sitting so close together, after all.”

He moved Stalwort’s pot into the back corner of the room, as far as possible from Moonblossom. He wasn’t sure what to do about her yet. He’d use the day to make up his mind. He uprooted Fuzzy, whispering words of comfort, and wrapped him up in a spare cloth before burying him outside next to Ember.

He went through his rounds of weeding, plagued by indecision. By midday he hadn’t made up his mind on what to do with Moonblossom. How much bigger would she be tomorrow? He couldn’t just get rid of her, could he? What would the fae think?

In the afternoon he passed through the town square on his way out to Lady Apple. He crossed paths with Orlia, who was tottering her way towards the tavern. At the sight of Russal, she froze, a dark scowl gathering on her face.

“Russal?” she asked. It was a demand for him to come over, which he did.

“Mother,” Russal said, “I’ve still got some work to—”

“I thought you said that necklace meant nothing!”

Russal blinked. “Necklace? What neck—” Then he felt it. The silver leaf necklace. He reached and felt it around his throat. But… how? He’d left it under the bed last night and hadn’t touched it since then. A wave of chills rippled down his spine.

“Well?” Orlia demanded.

He took off running towards the house.

“Russal!” his mother cried at his back. “Get back here!”

He ignored her—for now. He’d explain things later to her, after he’d dealt with whatever the hell was going on in his room. It had gone too far. He still had no idea what the fae wanted. Fuzzy might have been a mistake. But was the necklace? Had that been him? Or her? Didn’t matter. She was getting him in trouble with Orlia now and soon all of Thornbrook if he didn’t nip this in the bud. He’d had enough. He couldn’t house Moonblossom forever anyway.

When he reached the house, he dumped his half-finished bag of weeds into the burn pit, then brought the empty sack to his room. Moonblossom had reverted to a seed. But his gut lurched at the sight of his desk. Like the necklace, he’d left the wooden carving under the bed last night. Now the carving was sitting there, facing not the window sill, but the bed itself. The exact spot he slept.

“Gods,” he swore, turning to Stalwort, still in the corner of the room. “You were right, Stalwort. I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I’m going to fix it.”

He placed the necklace, the carving, and finally the seed—dug up gently from the pot—into his empty sack. He slung it over his shoulder and bounded out the door, avoiding the road into Thornbrook and cutting across briar country. A cold autumn wind whipped at him from the north, from the Deep Bramble.

At last he stood before its border. He waited for awhile, wondering if the fae might show herself. When she didn’t, he found a boulder and placed the seed, the necklace, and the carving atop its flat surface. “I’m sorry!” he called out to the forest. “I can’t do this anymore. I’ll get in too much trouble!”

No response.

After waiting awhile longer, he trudged back to the house. Orlia was waiting for him in his room, arms crossed and brow bunched up in rising anger. “Russal,” she growled as soon as he opened the door. “Explain yourself.”

Russal held up his hands. “It’s dealt with.”

“What’s dealt with?” She clawed at his jacket and rattled him. “You told me there was no woman! Then you strut around town flashing her charm around your neck like some kind of troupe whore?”

“No!” Russal said, gently but firmly pressing her away. “There’s no woman! I—I—I guess I liked the necklace a lot, but you’re right. Gives the wrong impression. So I threw it away.” He turned his jacket pockets inside out. “Look! See?”

Orlia eyed him up and down. Then she turned and pulled his pillow and blanket aside, looked under his bed, checked behind Stalwort. Russal just let her search until she was satisfied. Or at least, unable to find anything to argue with him about. With a final, wordless glare, she stormed out of the room and stomped across to her side of the house.

Russal glanced out the window. The sun was already beginning to set, and he found no energy to rush through the remainder of his daily work. A withering apathy had settled over his bones, and he slouched into bed. “She’s gone, isn’t she,” he whispered to Stalwort as he stared at the ceiling. “I sent her and all her things away.” He rubbed his stomach. “Looks like it’s just you and me, Stalwort. Just you and me. Now and forever.”

And yet he did dream that night. Back in the moonlit forest, surrounded on all sides by dark thicket and briars as sharp as swords. Her peals of laughter echoed from all directions, still as light and singsong as ever, which made it even more maddening. Her form flashed in the corner of his eye, and he kept spinning to see. Spinning and turning and twisting and stumbling across the cool, wet earth.

He awoke with a scream.

He screamed again when he saw his room in the harsh morning light. Moonblossom was back on the window sill as if he’d never taken her away. Her vines snarled across the walls and ceiling, sprouting thorns like daggers. Her fruits had grown as large as pumpkins, colored a blood-red hue and dripping with a gummy ichor. The flowers, too; they were all facing him, as if waiting to envelop his head in their bulbs.

Horrified, Russal swung his legs over the side of the bed—only to yelp again with a sudden, sharp pain in his legs. He looked down to see gashes all up and down his calves and feet. Only then did he realize that Moonblossom’s vines had wrapped around his legs overnight, and he’d unwittingly ripped them free of its thorny embrace. He seethed, clutching at the wounds as blood seeped through his fingers.

Bent over this way, he felt the silver leaf necklace dangling around his throat. “Shite!” he cried, ripping it off and throwing it at Moonblossom. He looked up and saw the wooden carving there on the desk, too, turned to face right at him. But the biggest blow fell when he spotted Stalwort in his corner. Moonblossom’s vines had grown across the floor, up over into his pot, and had wrapped around Stalwort. She crushed him to death, bits of pulpy fungal flesh oozing between the embrace.

Russal couldn’t even find his voice to cry out. His mouth was dry yet full, he now realized, of the taste of her—of cinnamon and lavender. He took a step forwards, then winced as his feet and legs cut against more thorns on the ground. What in the names of the woodland gods was happening? He had to get out of this, and now. He reached for his boots beside his bed and cringed as he pushed his scraped feet into them. Then he stepped across the room, across vines and around the flowers, and out the door.

Orlia was coming down the passage to him. “Russal!” she cried. “What’s wrong? Why were you screaming?”

Russal opened his mouth but no words emerged. Orlia clutched the sides of his arms, her face pale and creased with worry. But then, after a moment, she recoiled from him with a shriek of her own. She staggered against the wall as her face flushed from white to burning scarlet. He could almost see steam rising off her messy hair.

“How could you?” she choked. “I knew it. Knew it! Some woman has wrapped you around her finger and will take you away from me!”

She was staring at his neck and the top of his chest peeking through his jacket. He looked down and wanted to jump out of his own skin. Kiss marks, bite marks, and scratches covered his chest, shoulders, and neck. Marks of lovemaking. And yet he had no memory of any of it.

“Where is she?” Orlia demanded. She had recovered, stiffening herself up and clenching her fists into balls of fury. “Is she hiding in there? Oh, I’m going to kill her! I’m going to wring her scrawny little neck!”

Russal burst past Orlia, dashing across the house and out the door. His mother yelled after him, demanding he return at once. He ignored her and kept running, out into the briar country. A few moments later, he heard her scream echo through the house behind him. She must’ve discovered the inside of his room. He didn’t care what she did with the carving or the necklace or Moonblossom. They’d be back tomorrow morning, and maybe then her vines will have wrapped around his neck and strangled him in his sleep. Like Stalwort. Poor, poor, Stalwort.

No. He needed to put this to an end at the root of it all. The fae. It was all one giant misunderstanding. She probably thought he had rejected her, that he didn’t want to be with her, and was now taking out her jealous revenge. She needed to know it had nothing to do with that. That they couldn’t be together because of Orlia and the rest of Thornbrook. If he could explain it all to her, well, maybe all this would stop.

As he scrambled across the northern fields, he could hear the shouts of Orlia somewhere somewhere behind him. He didn’t care. Several farmers stared at him from a distance. He didn’t care. He pressed himself onwards, hissing through his teeth at each step on his wounded feet. He could feel the blood soaking the inside of his boots. More leaked from his upper calf, flicking off him as he ran, leaving a trail of bloody spots in his wake. He didn’t care.

At last he stood under Lady Apple at the edge of the Deep Bramble. He wrapped an arm around her truck and leaned against her a moment, catching his breath. The sun had disappeared behind the overcast sky, leaving the forest ahead cloaked in deep gloom.

“Gods flay me, but I have to go in,” he told Lady.

The wind rustled through her leaves. A response as good as any.

Swallowing dryly, he approached the border of the forest, walking along its edge until he found a gap in the briars and thorny vines. He pulled on his cracked leather working gloves from within his jacket—and then, pushing a curtain of spiky vines aside, stepped into the Deep Bramble.

Immediately he noticed how colder and darker it was just a few steps inside. The air was rife with the smell of mosses and molds and decaying leaves that crunched beneath his boots. Far ahead of him, deep within the darkest gloom of the Bramble, came the low groans and rumbles of shifting wood. Like the sound an old oak trunk makes when swayed by a powerful gale. But there was no wind in here.

As he left the weak shimmer of light at the edge of the Bramble, traveling inwards, the gloom wrapped all around him. The only sources of light were little clusters of glowing mushrooms, few and far between, casting a small sphere of frizzy purple light around themselves. Unable to think of a better way to navigate, Russal followed this ghastly trail of mushrooms through the Bramble, nervously thanking each one as he passed.

He trembled, and not because of the cold. His stomach and heart quivered in tight knots that threatened to wildly unspool at every unknown sound or sight. As he walked he looked all around, hoping to spot the fae and end this terrible trek. But she was nowhere to be found. No pale flashes in the corner of his eye. No tinkling laughter. It was not like his dream at all. He could see and hear small creatures skittering in the undergrowth around him, in the void of canopy above, but there wasn’t enough light to make them out. He couldn’t be sure, but it felt like they were following him.

He finally resorted to calling out to her. “Hello?” he cried. “It’s Russal! I just want to talk to you! Please!”

No response.

He wasn’t sure how long he wandered, calling out to the fae. There was no way to track time or distance. But at last he saw something. Between dark shapes of trees and vines and briar ahead, he spotted a bright, reddish purple glow. It was coming from a clearing or glade perhaps, far brighter than anything else. Like the living, beating heart of the Deep Bramble.

His pulse leapt and he picked up his pace. Had he found her? Was this where she lived? How would she react? He pressed onwards, ducking around webs of vines, squeezing through thickets, leaping over fallen logs. He was almost there now, and he wanted—

“Russal!”

It was not the voice of the fae, but that of Orlia, echoing through the forest.

He turned around and spotted the flickering light of a torch winking through the forest. He gasped, fear surging up into his throat like bile. He sprinted towards the flame, recklessly throwing himself through the undergrowth and earning cuts and scrapes in the process.

“Russal!” Orlia cried when he finally reached her. She must have run her way here, for she was heaving for breath, dripping with sweat, and covered in mud, cuts, and scrapes. “Thank the gods, there you are! I can’t—”

Russal snatched the torch from her hand and hurled it to the ground. Orlia shrieked with surprise as he stamped out the flame with his boot, leaving them in darkness save for hazy glow of a nearby mushroom.

“What have you done?” Orlia cried.

“What have I done?” he said. “What have you done, bringing open flame into here? This is their forest!”

She clawed at his jacket. “I just wanted to find you, Russal! I don’t know what the hell has gotten into you, or what’s happened to your room, but we need to leave this place!”

“I can’t! Not yet!”

“What? What ever do you mean? We need to ho home!”

He pushed her away from him. “No. You go home. Follow the mushrooms back. I need to talk to the fae.”

She clutched at his hands again. “Now you’re just talking mad, Russie. You ploughed a forest witch and now you’re under her spell! I’m not going to leave you here!”

He tried to shake her but she dug her nails into his skin. “No! Go home, mother!”

“Russal, enough! That is enough! We’re going home and that’s that, or else!”

There it was. The old threat. But rather than cower back, he found he had something solid inside him that hadn’t existed before. Something to stand on, and to resist his mother’s demand. He had to speak with the fae. Not only to stop her misguided rampage, not only for Fuzzy and Stalwort’s sake, but because there was something there between him and her, and he refused to let Orlia squander it.

“Leave me be!” he roared.

He shoved his mother away. She stumbled and fell into a patch of nettles, which clung to her clothing and immobilized her. “Agh!” she cried. The more she struggled, the more she tangled herself up. “Russal! Get me out of this at once!”

“No,” he said, and it felt good. “You just sit tight. I’ll be back for you when I’ve set things straight.”

She howled and screamed and cursed at him as he turned away, but he brushed these off. Squaring his shoulders and taking a deep breath, he resumed his trek to the heart of the Deep Bramble, which looked several stone throws away. Orlia yelled at his back the whole way, and soon it turned to sobbing, and then to nothing at all. He refused to cave in. He had to see this through.

Heart thumping in his throat, he stepped into the glowing glade.

He covered his eyes as they adjusted from the deep gloom into the bright, strange glows. Then he beheld the glade.

An intricate web of brambles covered the forest floor like the web of a spider, with flowers and fruits akin to Moonblossom’s scattered throughout. At the center was a ring of mushrooms, each as tall as a man’s knee. They practically burned with a feverish, reddish purple glow, as bright as a hungry bonfire. Jagged thorns and brambles glinted from the trees around and the canopy above. Nothing moved. It was as silent as the dead of winter.

He bristled, the hair on his neck rising. She was here. She was nearby. He knew it. He felt it. Like in his dream. But where? He tore his gaze around the glade, looking for her pale shape. The bare skin. The flutter of wings. Oh, how he wanted to see her. To smell her. To touch her. To feel her. His body ached with the want.

Where. Where was she? Where?

A shriek shattered the silence.

Russal froze. That was Orlia. It was not another angry, demanding shout. It was a screech of raw terror and horrendous pain. One that made his heart stop and his breath catch.

He whirled on his feet and sprinted towards his mother. His pulse pounded in his ears. Thorns raked at his arms and face and legs as he threw himself across the gloom. He couldn’t hear Orlia any more. What had happened? Had she cut herself getting out? Had stumbled and impaled herself on a large thorn? Had she—

She was right where he’d left her, and when he saw, he screamed.

His mother draped limp and lifeless across the patch of nettles. In the faint glow of the mushroom, he saw that thick brambles had erupted from the forest floor, piercing through Orlia’s backside and out through her chest where they blossomed in gory flowers. Some vines had punctured through the back of her skull, emerging out through her mouth and nostrils in bloody tendrils. Another had burrowed through one ear and out the other.

Her eyes had been left untouched. They were wide and full of terror and dead.

Russal recoiled, unable to look at her anymore. He stumbled and vomited onto the forest floor. Coughing and wiping his mouth, he clutched a nearby tree, thinking nothing of the thorns biting into his hands.

“Mother…” he whimpered. “Mother…”

Who had done this? Had it been his fae? Or another one, angered by the open flame? Or had it been the Deep Bramble itself? And whoever or whatever it was, why not him too?

His bloody hands slipped on the tree. He caught himself, but not after earning more gashes on his wrist and forearms. Did who or what matter? It was all his fault. He shouldn’t have left Orlia alone. He’d finally claimed a bit of freedom from his mother’s demands and this is what it had cost him. He didn’t know what to feel, it was all jumbling together inside of him.

He did know one thing, though, and it swept over him in a fresh wave of despair. He couldn’t go back. Assuming he was allowed to walk out of the Deep Bramble alive—which was a big if—the people of Thornbrook would grow suspicious of him. A few people had seen him and Orlia going towards the Deep Bramble. If he came out alone and bloodied, he’d be accused of all sorts of nasty things. Some would even be true, in a way. He’d be burned at the stake.

He glanced weakly at the torch he’d stomped out on the ground. Or, he thought, he could relight the torch and set as much as he could on fire. He had his knife and spare flint with him. He could do it. Either the fae or the forest would kill him for it, or he’d burn to death at his own hands. The angry part of him, wounded from his loss of Fuzzy and Stalwort and his mother, thought this was a perfectly suitable plan. He stumbled over and picked it up.

But the other part, the part that had finally won him a taste of freedom, that so desperately wanted her, objected. He looked towards the glowing glade in the distance. Fleeing the forest or burning it all down—that was the coward’s way out. The fool’s way out. He was still alive, wasn’t he? What if it was a sign? What if his faemark had fated him for this from the very beginning, and there was still a chance? Still a chance to see her? Still a chance for some good to come of all this? What if she did love him, and they could be together? Would that not be better than a bitter, fiery end?

He found himself staggering towards the glade.

The ring of mushrooms seemed to glow even brighter at his return. Torch still in hand, he stepped across the brambly floor of the glade and hovered at the edge of the ring. There were old folktales, too, of these rings. What they meant. Where they led. What you would find on the other side. And when you made that leap, there was no coming back, either.

But to him, in this moment now, it was clear what was inside the ring.

Her.

She was so close. He could practically hear her silvery laugh, smell her fragrant scent, see her beautiful form. She was on the other side, waiting for him.

And, well, maybe that was enough.

He dropped the torch and stepped into the ring.

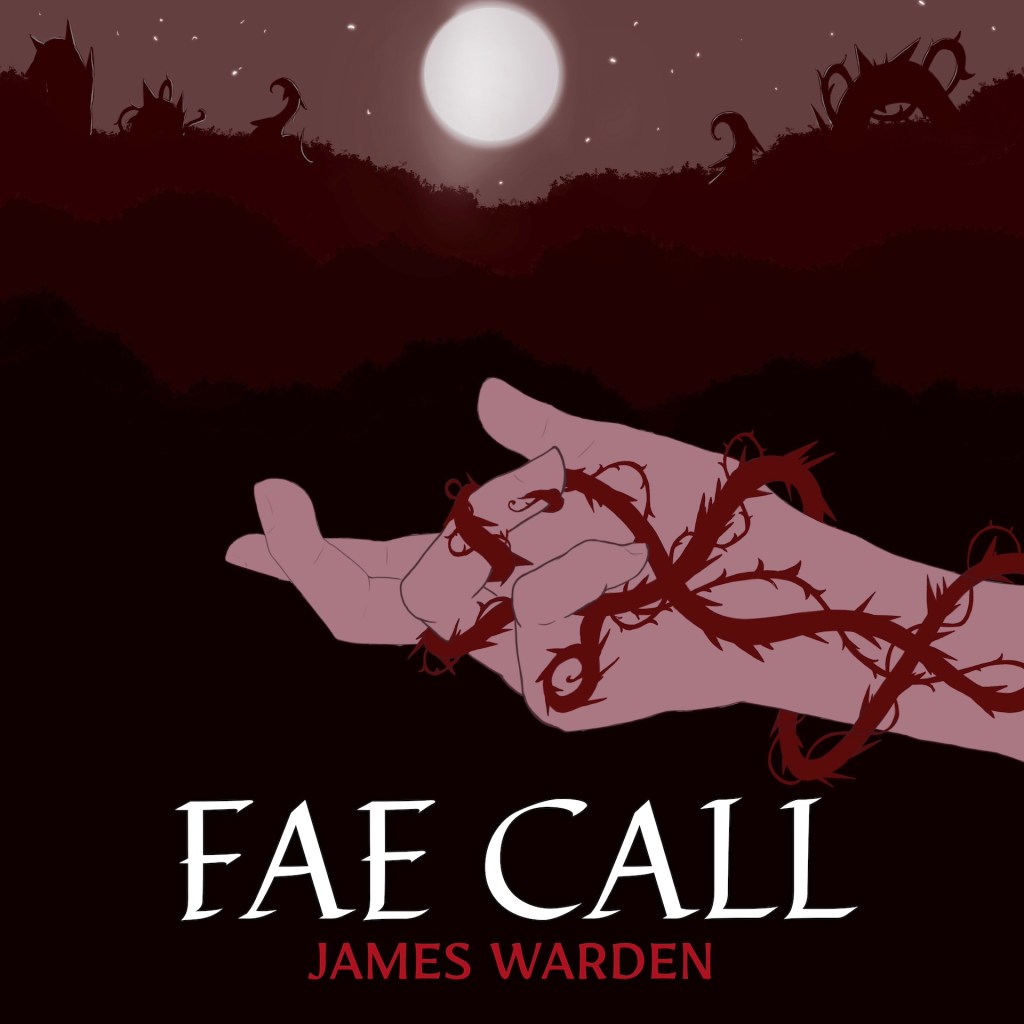

Join the newsletter

Thanks for reading! If you liked what you read, consider subscribing to the weekly newsletter and get:

- Early access to Lorellum Fantastica Entries

- Updates on new stories, artwork, and more

- Guaranteed faster delivery than raven, pony express, and dragonflight.